Courtesy of Library and Archives Canada

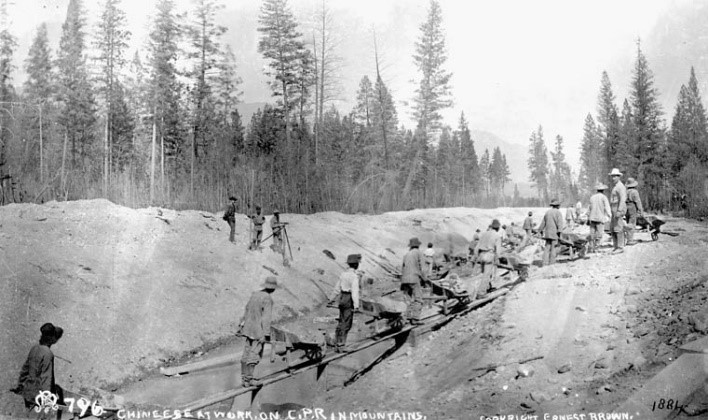

Chinese workers and the Canadian Pacific Railway

Before I even tell you about Chinese workers at CPR, let me start by explaining the situation they had arrived in. British Columbia in the late 1850s already had a sizeable Chinese population following the gold rush. So there was already rampant racism, perfectly immortalized in the very degrading depictions of Chinese people in editorial illustrations. And in classic xenophobic tendencies, white workers in B.C. were afraid that Chinese workers would take away their jobs since they were willing to accept lower wages.

So, of course, the wages at Canadian Pacific Railway were very meager and the work was way too dangerous. So dangerous that many Chinese workers just did not make it home. There wasn’t even much medical aid available. In fact, it’s estimated that three workers died for every mile of track laid. To make matters worse, once Chinese workers had finished building the railway, a head tax (and later the Chinese Exclusion Act) was imposed on all Chinese migrants entering Canada, further disenfranchising them and excluding them from many businesses and professions.

Read more about the Chinese railway workers here: The Ties that Bind

Courtesy of Glenbow Archives, ND-3-6226

Chinese Laundry Workers’ Union: Sai Wah Tong

The legal exclusion and constant increases to the head tax (it hit $500 in 1903!) made it hard for Chinese people to earn a living in Canada. And so they went where work was in demand: laundries. But work in the then growing laundry industry was constant and extremely physical. We’re talking 18 hour workdays – workdays meaning literally every day.

So they formed their own union and demanded better for themselves: higher wages, two-hour lunch breaks, 13-hour workdays, and days off on Sundays. After one strike in November of 1906, their demands were met.

Read more about Chinese laundries here: Sai Wah Tong

Courtesy of The Chinese Canadian Military Museum

Roy Mah

A one-day turnaround unsurprisingly inspired other Chinese workers to create their own unions. There was the Chinese Railroad Workers, the Chinese Canadian Labour Union, the Chinese Cooks’ Union, and the Chinese Restaurant Workers Union. Instead of tolerating exclusion, Chinese-Canadians were now empowered to mobilize and fight for better conditions, which eventually led to future activists fighting against discrimination and the successfully demanding to repeal the Chinese Exclusion Act.

Arguably the most notable of these Chinese activists was Roy Mah, a leader in Vancouver’s Chinese-Canadian community. After World War II, he was credited with bringing as many as 2,500 Chinese-Canadian workers into the union: “I always want to fight for a cause, especially for a just cause. Fight for civil liberty, fight for equal rights, fight for a fairer society.”

Read more about Roy Mah.

Courtesy of Vancouver Public Library

Sikh sawmill workers & Darshan Singh Sangha

Ever humble, Roy Mah notes himself as “only an organizer,” and instead quickly highlights another notable Asian leader in labour activism: “Darshan was part of the upper layers of the leadership.” He’s talking about Darshan Singh Sangha, the Secretary General of the International Woodworkers of America. Darshan migrated to B.C. in 1937, and worked alongside many Sikh immigrants from the Punjab region in India who helped build up B.C.’s timber industry since the early 1900s. He experienced right away the discrimination and poor working conditions Sikh sawmill workers had faced for years.

So he joined the International Woodworkers of America, served as their Secretary General, led a worker’s march to Victoria in 1946, and then led a strike for 37 days. His Punjabi union pamphlets inspired and motivated not only Sikh sawmill workers, but other Asian woodworkers as well. Their united efforts granted them legal rights to an eight-hour work day, increased pay, and better working conditions. When he finally resigned, Darshan reminded everyone in his letter the importance of solidarity: “One of the greatest achievements of the IWA was the uniting of all woodworkers – white, Indian, Chinese, Japanese – irrespective of race and colour.”

Read more about Darshan Singh Sangha and the Sikh sawmill workers in BC.

Courtesy of IWA Archives

The first Japanese-Canadian union & Joe Miyazawa

I think it’s time to address a very important question you probably have been wondering: why did all these Asians create their own unions? Well, when I said rampant racism, I did mean everywhere. When I said exclusion, I did mean from everything. Unions were not any different. Asians were unfortunately excluded from unions. That’s why they created their own.

The Japanese were no different. In 1919, 200 Japanese-Canadian workers at the Swanson Bay Mill went on strike to fight for equal pay with white workers. This led to the creation of the Japanese Camp and Mill Workers Union, the first Japanese-Canadian labour union, which Joe Miyazawa’s father was heavily active in. This union is what motivated Joe Miyazawa to join the International Woodworkers of America as an organizer at the Kamloops sawmill where many Japanese-Canadians found work. He eventually became associate director of research. Once he finally retired from the union, his work wasn’t done. In fact, he shifted from labour activism to the larger stage of fighting for human rights by combatting racial discrimination in Canada.

Read more about Joe Miyazawa.

Current Asian activists, including PSAC’s NEW National President!

It is important to recognize how labour activism eventually leads to the very fundamental fight against discrimination. The history of Asian labour activism in Canada really proves to us that solidarity and advocacy relies on people banding together under this common cause. It is within the fight for this cause and within the coming together of different kinds of people that you begin to see the actual breaking of barriers.

Today, we understand the importance of this solidarity and see it in the actions of current Asian labour alliances (Asian Canadian Labour Alliance | Migrant Workers Alliance for Change | Migrante Canada). And of course, we can see it in our very own union through Sharon DeSousa, newly elected as PSAC’s first racialized National President. It’s inspiring to see how far Asians have come in this country: from being constantly excluded even in labour unions, to now having an Asian woman lead one of Canada’s largest unions. I am uplifted by those that came before us and those that stand in front of us as our leaders, and I am empowered by how we to continue to shift history.